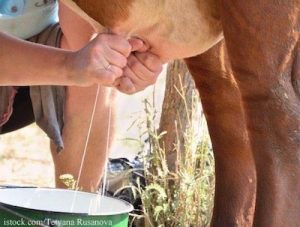

A study published in the April issue of Clinical Infectious Diseases looked at the 2012 Campylobacter outbreak linked to raw milk produced at the Family Cow dairy in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. The study’s authors say this outbreak “demonstrates the ongoing hazards of unpasteurized dairy products.” That outbreak sickened at least 81 people in four states.

The sale of raw milk is legal in Pennsylvania, although transporting raw milk for sale across state lines is illegal. Dairy farms which produce and sell raw milk in that state must be inspected by public health officials annually and test their products two times a month for coliforms and standard plate counts. Biannual milk culturing for bacterial pathogens is also required. Despite these rules, during the time period of 2007 to 2011, 15 unpasteurized milk-related disease outbreaks were identified in Pennsylvania. At least 233 people were sickened in those outbreaks.

The sale of raw milk is legal in Pennsylvania, although transporting raw milk for sale across state lines is illegal. Dairy farms which produce and sell raw milk in that state must be inspected by public health officials annually and test their products two times a month for coliforms and standard plate counts. Biannual milk culturing for bacterial pathogens is also required. Despite these rules, during the time period of 2007 to 2011, 15 unpasteurized milk-related disease outbreaks were identified in Pennsylvania. At least 233 people were sickened in those outbreaks.

On January 24, 2012, the Pennsylvania Department of Health (PADOH) received word that people had been sickened after consuming unpasteurized milk from a PDA-certified dairy. Family Cow, the dairy in question, immediately and voluntarily suspended unpasteurized milk sales. Epidemiological and environmental testing began; the dairy was inspected on January 30, 2012 and February 6, 2012. Raw milk from the dairy was obtained from consumers and the outbreak strain of Campylobacter was found in those unopened containers. The cows at the dairy were not tested for pathogens.

All patients in this outbreak, except for one family member who probably contracted the infection from another person, drank unpasteurized milk from Family Cow dairy. An additional 67 probable cases were identified in the four states associated with the outbreak. Ten people were hospitalized in this outbreak.

Family Cow dairy is among the largest sellers of unpasteurized milk in Pennsylvania. Inspections revealed the only deficiency at the dairy was a broken mechanical milk bottle capper. Employees capped the bottles manually. In mid-January, the temperature of the water used to clean equipment and piping was 50 degrees cooler than the recommended temperatures of 160 to 170 degrees F, which was another deficiency.

The study’s authors state that “the number of identified cases [in this outbreak] is likely an underestimate. [Editor’s note: the multiplier for Campylobacter outbreaks is 38. That means as many as 3000 people may have been sickened in this one outbreak.] This is because probable cases had to be epidemiologically linked to a confirmed case and other ill persons might not have heard of the outbreak, were not tested, or were tested too late in the course of illness to still be shedding the organism. Finally, ill persons might have elected not to disclose unpasteurized milk consumption. Purchasers residing in other states might not have reported illness if they thought that carrying milk across state lines was illegal.”

The researchers continue, “while it might be possible to reduce the risks associated with unpasteurized milk consumption with further testing, consumers can never be assured that certified unpasteurized milk is pathogen-free, even when from a seemingly well-functioning dairy. The only way to prevent unpasteurized milk-associated disease outbreaks is for consumers to refrain from consuming unpasteurized milk. This outbreak demonstrates the importance of pasteurization and the ongoing need for consumer education to specifically highlight the risk of serious illness from unpasteurized dairy products and the need to avoid these products. This is especially important for consumers at high risk for complications from infections (eg, pregnant women, immunocompromised persons, and young children).”