Hospital listeriosis outbreaks, such as the one in Kansas linked to Blue Bell ice cream, can be difficult to detect and especially dangerous because 90 percent of Listeria-related illnesses fall on expecting mothers, infants, seniors and others who are immuno-suppressed. In 2010, a determined group of epidemiologists at the Texas State Department of Health Services launched an investigation into a puzzling outbreak that killed five hospital patients over a period of seven months at various hospitals in the central portion of the state. The team wrote about their work in the Oxford Journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases, raising questions about why hospitals don’t do more to protect vulnerable patients from food poisoning.

The same agency recently helped to confirm that Blue Bell ice cream contained the exact same strain of Listeria monocytogenes that killed three patients at Via Christi St. Francis Hospital in Wichita, Kansas. Like the Texas outbreak of 2010, the victims were sickened by food served in the hospital while they were being treated for other conditions. The CDC and FDA have linked the Kansas hospital Listeria outbreak to milkshakes made from contaminated Blue Bell “Scoops.” Listeria lawyers for Kansas patients will rely on the findings as claims and litigation unfold.

The same agency recently helped to confirm that Blue Bell ice cream contained the exact same strain of Listeria monocytogenes that killed three patients at Via Christi St. Francis Hospital in Wichita, Kansas. Like the Texas outbreak of 2010, the victims were sickened by food served in the hospital while they were being treated for other conditions. The CDC and FDA have linked the Kansas hospital Listeria outbreak to milkshakes made from contaminated Blue Bell “Scoops.” Listeria lawyers for Kansas patients will rely on the findings as claims and litigation unfold.

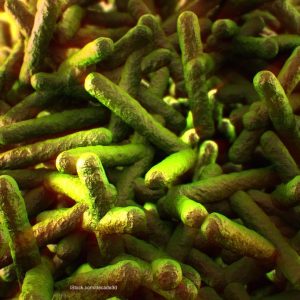

Invasive listeriosis sickened 10 immuno-compromised patients at seven Texas hospitals between January and August, 2010. The median age of these patients was 80 years and five of them died. By early May, authorities knew they had a serious outbreak involving at least seven patients in four hospitals. The outbreak team used food history questionnaires to zero in on common denominators, finding strong correlations to chicken salad and cold sandwiches. Food sampling and testing focused on raw and cooked poultry products, with positive results coming from freshly made chicken salad served cold.

The next step in the investigation was to focus on ingredients in the chicken salad, leading the team to a fresh produce processing facility. Through distributors, the plant sold diced celery to every hospital that hosted an outbreak patient. The inspectors collected 10 vacuum-sealed final product samples of celery and seven of them tested positive for the outbreak strain of L. monocytogenes. The team wrote that the processing facility had “inadequate produce handling and cleaning techniques.” By then it was October, but the finding stopped the outbreak from spreading. Moreover, the health agency issued an Emergency Order of Closure and Recall for all products with production dates from January 2010 forward. The company closed permanently in February 2011.

“One of the difficulties of hospital-acquired foodborne illness outbreak investigations is that foods consumed by patients are frequently not reported in medical records,” the Texas group wrote in their Oxford Journal piece. “A survey of New York City hospitals found that 57% of hospitals do not maintain a record of foods ordered by patients. Furthermore, there are no uniform guidelines regarding serving ready-to-eat produce to immuno-compromised hospitalized patients.”