Food Safety attorneys at Food Poisoning Bulletin underwriter, Pritzker Hageman, reported that the Summer of 2018 was one of their busiest ever because of the sheer volume of Cyclospora victims needing their legal help. However they state that, despite Cyclospora related illnesses being so prevalent in the summer months, when they mention it, they are usually met with the question: “So…what is Cyclospora?”

Cyclospora is a protozoan parasite that causes severe gastroenteritis in humans called cyclosporiasis.

There’s a reason that Cyclospora doesn’t have the same household name that more common bacterial pathogens like Salmonella and E. coli do: it hasn’t been causing illnesses in the continental United States for nearly as long.

The parasite Cyclospora was first described by Dr. Ashford, a British parasitologist, in 1979. He found the parasite in stool samples from sickened people in Papua New Guinea in 1977 and 1978. In the 1990s, Cyclospora garnered increasing interest from the scientific and public health communities after it was identified as the cause of outbreaks of diarrheal illness in the United States. Since then, scientific understanding of Cyclospora’s source and infectious process has grown substantially.

Humans contract Cyclospora infections from eating food or drinking water contaminated with Cyclospora. Contamination of food often occurs when produce is irrigated or washed in water contaminated with human feces. Cyclospora uses the human body to complete part of its reproductive life cycle.

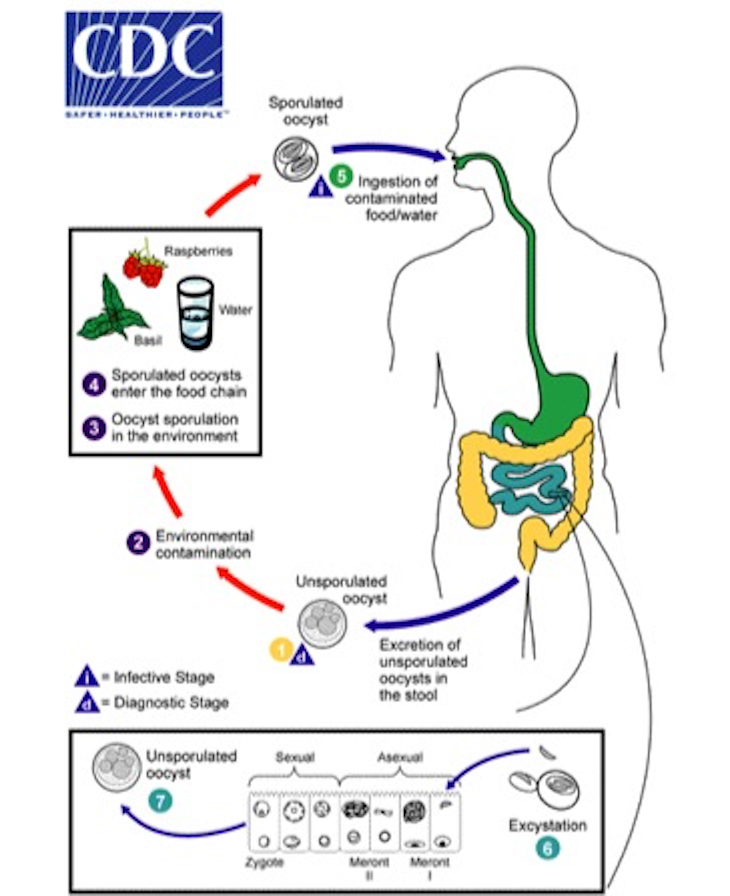

The CDC outlines the life cycle of Cyclospora in the following diagram:

Cyclospora oocysts are excreted in the feces of infected people. Fresh excreta containing unsporulated (immature) oocysts is noninfectious. Instead, the oocysts must sporulate in order to become infectious. Therefore, Cyclospora is not known to be transmitted directly from person-to-person.

Oocysts sporulate within 1-2 weeks, depending on environmental conditions. After sporulation, the sporont becomes two sporocysts, each containing two elongated sporozoites. After sporulation, the Cyclospora organism is infectious, and when consumed by humans, causes illness. Put simply, feces must contaminate food or water and then remain there long enough to sporulate in order to cause illness.

Within the human body, oocysts excyst, or emerge, in the gastrointestinal tract, freeing the sporozoites, which invade the epithelial cells of the small intestine. Inside the cells of the small intestine, they undergo asexual multiplication and sexual development to mature into oocysts, which are shed in stools.

Cyclospora is not endemic to the United States. The illness is most common in tropical and subtropical regions, and it is more common in summer months. Numerous previous outbreaks of Cyclosporiasis in the United States have been associated with consumption of fecally-contaminated fruits and vegetables, including raspberries, mesclun, basil, lettuce, and cilantro.

For example, over the last several years, cilantro grown in Puebla, Mexico caused so many illnesses in recent years that public health officials began to examine the source of the contamination more closely. From 2013 to 2015, FDA and Mexican officials inspected 11 farms in Mexico, including 5 that had been associated with Cyclospora outbreaks in the U.S. Their findings prompted the issuance of an import alert (which was recently updated on October 2, 2018):

Conditions observed at multiple such firms in the state of Puebla included human feces and toilet paper found in growing fields and around facilities; inadequately maintained and supplied toilet and hand washing facilities (no soap, no toilet paper, no running water, no paper towels) or a complete lack of toilet and hand washing facilities; food-contact surfaces (such as plastic crates used to transport cilantro or tables where cilantro was cut and bundled) visibly dirty and not washed; and water used for purposes such as washing cilantro vulnerable to contamination from sewage/septic systems. In addition, at one such firm, water in a holding tank used to provide water to employees to wash their hands at the bathrooms was found to be positive for C. cayetanensis. Based on those joint investigations, FDA considers that the most likely routes of contamination of fresh cilantro are contact with the parasite shed from the intestinal tract of humans affecting the growing fields, harvesting, processing or packing activities or contamination with the parasite through contaminated irrigation water, contaminated crop protectant sprays, or contaminated wash waters. [Emphasis added]

This report highlights the importance of verifying the safety of imported produce, particularly produce grown in Mexico, to ensure it is not contaminated with Cyclospora. However, even domestic produce samples have tested positive for Cyclospora, a sign that we may be facing an even greater threat in the years to come.

Responsible fresh produce producers should take steps to produce food free of fecal matter and dangerous organisms like Cyclospora, like creating and following a farm food safety program. Because Cyclospora is extremely difficult to kill—even with bleach—growers must work to keep contaminated feces off food products to begin with.

Pritzker Hageman food safety lawyers have represented many clients who have been sickened with cyclospora infections, as well as E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Listeria monocytogenes.