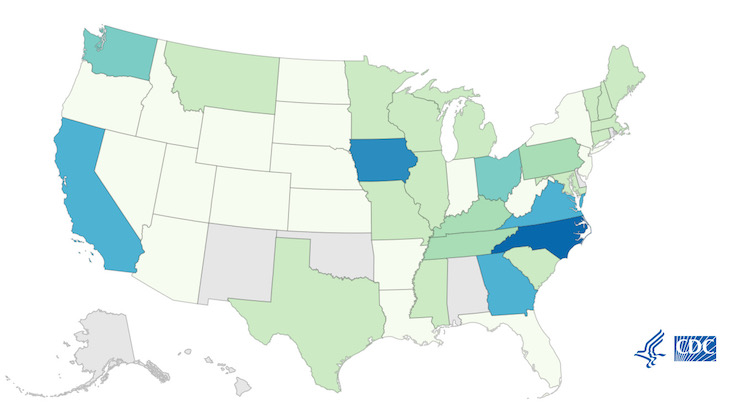

A Salmonella outbreak linked to backyard poultry has sickened at least 163 people in 43 states, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Thirty-four people have been hospitalized because they are so sick. All people sickened by live poultry in this country in the last 10 years add up to almost 7,000 illnesses.

The case count by state is: Arizona (2), Arkansas (2), California (9), Colorado (2), Connecticut (3), Florida (1), Georgia (9), Idaho (1), Illinois (3), Indiana (2), Iowa (11), Kansas (1), Kentucky (5), Louisiana (1), Maine (3), Maryland (3), Massachusetts (3), Michigan (4), Minnesota (3), Mississippi (4), Missouri (4), Montana (4), Nebraska (2), Nevada (1), New Hampshire (3), New Jersey (2), New York (2), North Carolina (13), North Dakota (1), Ohio (7), Oregon (2), Pennsylvania (6), South Carolina (4), South Dakota (1), Tennessee (6), Texas (4), Utah (2), Vermont (3), Virginia (9), Washington (8), West Virginia (1), Wisconsin (4), and Wyoming (2). The patient age range is from less than 1 to 87 years. Of the 91 people interviewed, 88% said they had contact with backyard poultry before they got sick.

Of 109 people sickened in this Salmonella outbreak linked to backyard poultry who gave information to investigators, 34, or 31%, have been hospitalized, which is high for a Salmonella outbreak. The average hospitalization percentage for these outbreaks is 20%.

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) performed on patient isolates found that the bacteria are closely related genetically. That means that people in this outbreak likely got sick from the same kind of animal. On April 15, 2021, Ohio officials collected samples from a sick person’s ducklings for testing. WGS showed that the bacteria, Salmonella Hadar, was closely related to bacteria from sick people.

The bacteria also showed antibiotic resistance. Among bacteria taken from 125 sick people’s samples and 1 animal sample, 63 (50%) were predicted to be resistant to one or more of the following antibiotics: ampicillin (1%), chloramphenicol (1%), streptomycin (50%), sulfamethoxazole (2%), and tetracycline (48%). This can make these infections more difficult to treat.

People can get sick from backyard poultry in several ways. The animals shed the bacteria in their feces, which can then get on their feathers and the environment they live in. If you touch these birds or anything in the area around them and then touch your mouth or food, you can get sick.

Children are especially vulnerable to this mode of transmission because – let’s face it – baby chicks and ducks are cute. Everyone has seen children cuddling and kissing these birds.

But you can prevent infections from backyard poultry by following a few rules. Always wash your hands with soap and water after handling the birds, their eggs, or anything in the area where they live and roam. Do not snuggle or kiss the birds and don’t eat or drink around them. And keep your supplies used to care for the flock outside. Supervise children around the birds and don’t let kids under the age of five handle or touch chicks, ducklings, or other live poultry.

It’s worth noting that the number of people in any given Salmonella outbreak is much higher than the official case count, because many people recover without medical care and are not treated. In fact, the multiplier for Salmonella outbreaks, which is the number investigators multiply the outbreak total by to get and estimate of the actual case count, is 30.3. That means there could be almost 5,000 people ill in this one outbreak.

And the risk with any Salmonella infection is that even after a patient recovers completely, they can have long term health complications. These complications can include high blood pressure, reactive arthritis, endocarditis, and irritable bowel syndrome. So even if your symptoms are mild, see your doctor to make sure this infection is recorded on your chart.

Symptoms of a Salmonella infection include a fever, nausea, vomiting, abdominal and stomach pan and cramps, and diarrhea that may be bloody. Symptoms can begin 6 to 72 hours after exposure. Most people get better within a week, but some do become ill enough, usually through sepsis or dehydration, to need hospitalization.