For the last 25 years, the USDA has been trying to reduce Salmonella illnesses by testing for the presence of the bacteria on poultry at processing plants. On the face of it, this seems like a solid plan. According to the CDC, Salmonella causes more foodborne illness than any other bacteria, about 1.35 million cases each year, and contaminated poultry accounts for about 23 percent of those illnesses.

But something strange happened.

Two decades of test results showed an overall reduction in the occurrence of Salmonella on poultry products, but the percentage of Salmonella illnesses linked to poultry didn’t decrease. In fact, it went up.

And while the number of Salmonella illnesses linked to poultry increased, so did the severity thanks to the growing prevalence of dangerous, antibiotic-resistant Salmonella strains, as ProPublica recently reported.

Now the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) is rolling out a new plan to try and tackle the poultry industry’s Salmonella problem. “Time has shown that our current policies are not moving us closer to our public health goal. It’s time to rethink our approach,” USDA Deputy Under Secretary Sandra Eskin said in a recent statement. Three key aspects of the plan are preharvest (on-farm) controls, measuring the quantity of Salmonella found on a sample, not just its presence, and focussing on Salmonella serotypes that cause the most harm.

Will it work?

USDA’s Current Salmonella Reduction Plan

If all three aspects of the new plan are enacted, it would be a significant departure from the agency’s current approach. Meat and poultry have long been identified as major sources of foodborne illness. By the 1990s, consumers were clamoring for a more proactive approach to controlling bacterial contamination instead of investigating what “went wrong” after each outbreak occurred.

So, in 1996, the USDA finalized the Pathogen Reduction HACCP rule requiring all “meat and poultry establishments to prevent or eliminate contamination of meat and poultry products with disease-causing, that is, pathogenic bacteria, as well as to prevent, or to reduce to an acceptable level, contamination with other biological, chemical, and physical hazards.”

HACCP stands for Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point, a process developed by Pillsbury Co. for NASA in the late 1960s. “The program provides a proactive approach to food safety by requiring plants to identify all potential avenues of contamination (hazards) and determine how to control, reduce, and/or prevent them to ensure that safe food will be produced,” according to an overview of the rule published by Kevin Keener, Ph.D., P.E. Food process engineer, Extension specialist, and associate professor of food science at Purdue University.

Designed by Pillsbury, Space Food Sticks were the first solid food consumed by a NASA astronaut aboard Aurora 7 in 1962. They were also onboard several Apollo and SkyLab missions.

“By any measure, our country has done a better job preventing foodborne illness in outer space than we have here on planet Earth,” said Food Safety Attorney and Food Poisoning Bulletin Publisher Fred Pritzker.

Measurement does seem to be a big part of the problem.

Allowable Levels of Salmonella

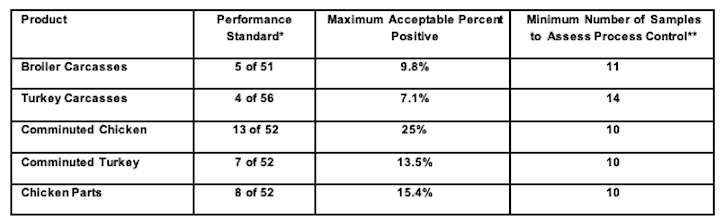

Since its inception, the focus of the PR/HACCP program has been on reduction rather than elimination. Before the rule was finalized, the USDA created performance standards or, as many consumers are horrified to discover, allowable percentages of Salmonella on poultry products.

USDA FSIS chart of current poultry performance standards.

These testing levels fall into a three-tiered system reflecting whether the meat or poultry being produced at slaughterhouses meets, exceeds, or fails to meet those standards. Meat and poultry products are allowed into commerce regardless of the test level, but to create an incentive for companies to try and reduce the number of positive tests, the agency committed to publishing quarterly results online.

If an establishment failed to meet performance standards three times it would “constitute a failure to maintain sanitary conditions and failure to maintain an adequate HACCP plan for that product, and will cause[USDA’S] Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) to suspend inspection services,” the rule stated. Pulling inspectors from a plant shuts down production.

The program was rolled out in stages over a two-year period starting in January 1998 with testing for E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella at large establishments. Within months, the three-strikes-we’re-out rule faced a legal challenge that would essentially strip the USDA of its only enforcement power.

Supreme Beef Processors Inc. v. United States Department of Agriculture

In November 1998, USDA FSIS began a round of testing at Supreme Beef Processors, Inc. a Dallas-based meat processor that supplied beef to the National School Lunch Program. After four weeks, results showed 47 percent of samples tested were contaminated with Salmonella, according to the lawsuit. (The performance standard for ground beef is 7.5 percent.)

USDA FSIS issued a noncompliance report and told the company to take immediate action to meet the performance standard. The company asked for, and was granted, a delay to the start of the second round of testing.

On April 12, 1999, the second round of tests began. Six weeks later, USDA FSIS again informed the company that it was not in compliance with performance standards as test results showed 20.8 percent of samples tested were positive for Salmonella, according to the lawsuit. The company appealed the noncompliance report saying its own tests showed just 7.5 percent of the samples were positive for Salmonella. USDA FSIS denied the appeal.

A third round of tests that began on August 27, 1999, ended five weeks later with USDA FSIS notifying Supreme Beef that it had not met performance standards. On October 19, 1999, the agency notified the company that it was canceling the School Lunch Program contract and intended to pull inspectors unless it could “demonstrate that its HACCP pathogen controls were adequate or to show that it had achieved regulatory compliance,” by October 25, 1999, according to the lawsuit.

Supreme Beef said it could come into compliance if given six more months instead of six more days. But the company did not supply specifics on how it planned to do that, so USDA FSIS went ahead with its plans to pull inspectors from the plant.

On the day this was to take place, Supreme Beef filed a lawsuit against the USDA alleging the agency had overstepped its regulatory purview, that Salmonella isn’t an adulterant because it is naturally occurring, and that the presence of Salmonella on finished meat samples is not a proxy for adequate pathogen controls at processing plants. The company asked for a temporary delay in the agency’s plans to pull inspectors from the plant. The district court granted both of the company’s motions.

The USDA appealed, but the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the lower court’s ruling. The federal agency charged with regulating the country’s meat and poultry supply lost its only enforcement tool. So, for the last 20 years, USDA FSIS has been testing poultry samples for Salmonella and publishing the results online.

When there is a suspected outbreak, the agency won’t ask a company to issue a recall unless an unopened package of meat or poultry taken from an outbreak patient’s home tests positive for the specific strain of Salmonella linked to the outbreak according to genetic tests. A series of outbreaks linked to Foster Farms chicken exemplifies all of the flaws in this system. But it’s just one of many.

Salmonella Illnesses on the Rise

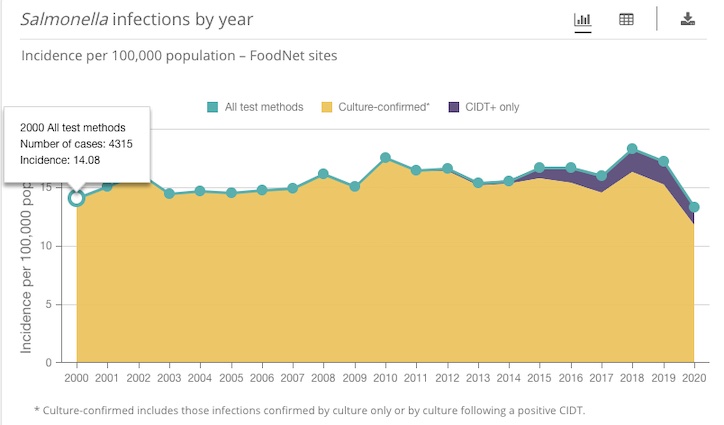

In 1998, the year the USDA FSIS pathogen testing HACCP began, the incidence of Salmonella infections per 100,000 population was 13.61, according to CDC data. Three years later, in 2001, the year the Fifth District Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Supreme Beef, stripping USDA FSIS of its enforcement power, the rate was 15.04. By 2018, it reached an all-time high of 18.29 and fell off to a rate of 17.2 in 2019.

As a side note, the rate was 13.33 in 2020, but we’re sidestepping that year because of anomalies caused by the pandemic. In 2020, there was a 26 percent decrease in the incidence of illness from all foodborne pathogens, the largest single-year decrease in the 25-year period that the CDC has gathered such data, according to a recent study. Researchers said this was due to a number of pandemic-related factors.

CDC graph Salmonella illnesses 2000-2020

Over the last two decades, the rate of Salmonella illnesses climbed even after performance standards were adjusted, twice.

In 2011, new performance standards were put in place after the Obama Administration charged USDA FSIS with the task of cutting the risk posed by poultry products. The rate for whole chicken was cut by more than half, from the 20 percent standard for broilers set in place since the program’s inception, to 9.8 percent. In 2016, years after consumers showed they were more interested in buying chicken breasts, thighs, or wings than whole birds, USDA FSIS set performance standards for chicken parts for the first time, 15.4 percent.

The fact the rate of positive Salmonella tests on chicken went down during the same period that Salmonella illnesses linked to chicken increased is an indicator that measuring for the presence of Salmonella isn’t enough, studies show. Testing should differentiate the quantity of Salmonella present and the strain because some strains are known to cause serious illness. And increasingly, they are developing a resistance to antibiotics.

Antibiotic Resistance on the Rise

The same CDC study that tracked the 26 percent decrease in illness from all foodborne pathogens, noted that even during the pandemic, there were notable developments in the incidence of Salmonella illness from poultry. For example, illnesses linked to Salmonella Hadar increased 617 percent due in large part to huge outbreaks linked to backyard poultry flocks. And illnesses associated with two Salmonella strains, Infantis and Newport, held steady. The “stable incidences despite the pandemic suggest that they might have increased otherwise,” the researchers said. Also noting “rising multidrug-resistant Salmonella Infantis infections have been linked to consumption of chicken.”

The ProPublica report revealed for the first time that a deadly outbreak linked to a variety of chicken products contaminated with multidrug-resistant Salmonella Infantis has actually been ongoing since 2018, even though the CDC declared it over in 2019. ProPublica reporters discovered that the CDC gets dozens of reports of illness linked to this strain each month. And that USDA FSIS inspectors have come across the strain an average of two times each day in 2021.

During their investigation of the outbreak in 2018 and 2019, the CDC and USDA FSIS found the outbreak strain of Salmonella Infantis in 76 samples collected from live chickens, from raw chicken pet food, and from chicken processing facilities. Multiple brands were implicated, but none was ever named. And no recalls were issued.

“Many infections are now caused by a new, highly resistant strain [of Salmonella Infantis] found in chicken,” according to a CDC study published last year. In the late 1990s, Salmonella Infantis was the ninth-most-common Salmonella serotype associated with illness. In 2019, it was the sixth-most-common. For the first quarter of fiscal 2021, it’s at #1.

And Infantis is just one of the antibiotic-resistant Salmonella strains. A recent study of drug-resistant Salmonella infections shows an increase of 40 percent from rates measured 2004-2008 compared with rates in 2015-2016. “Serotypes I 4,[5],12:i:- and Enteritidis were responsible for two-thirds of this increase,” researchers said.

On the Farm

One proven method of combatting serious illness from particularly virulent Salmonella strains is vaccinating flocks. In the U.S., this practice was effective at reducing Salmonella Typhimurium illnesses. Great Britain has been vaccinating chickens against both Salmonella Enteritidis and Salmonella Typhimurium since 1993. By 2011, the rate of Salmonella Enteritidis infections among British citizens had decreased 99 percent in those countries

Last year, the director of The Pew Charitable Trusts’ work on food safety, wrote an article called Vaccines for Poultry Are Crucial for Preventing Salmonella Contamination. “Widespread administration of existing and new Salmonella vaccines could help bring down contamination rates in poultry to the extent needed to reduce foodborne infections. Moving the nation toward that goal requires that producers use these measures, especially on high-risk farms, and retailers can contribute by insisting that their poultry suppliers apply these effective food safety tools, “ she wrote.

The author, Sandra Eskin, is now the USDA Deputy Under Secretary who said it’s time for the agency to rethink its approach to the poultry industry’s Salmonella problem. “For the millions of Americans who have been sickened by Salmonella, and the safety of our nation’s food supply, let’s hope she can turn her advocacy into action,” said Pritzker.