For the fifth straight year, more than 1,000 Americans developed cyclosporiasis, a parasitic infection, from food sold, and some of it grown, in the U.S. Decades ago, these Cyclospora infections, which are characterized by frequent bouts of explosive diarrhea, were associated with travel to underdeveloped countries with tropical or subtropical climates. But the sharp rise of non-travel-related (NTR) illnesses since 2013 gave birth to a Cyclospora season in the U.S.

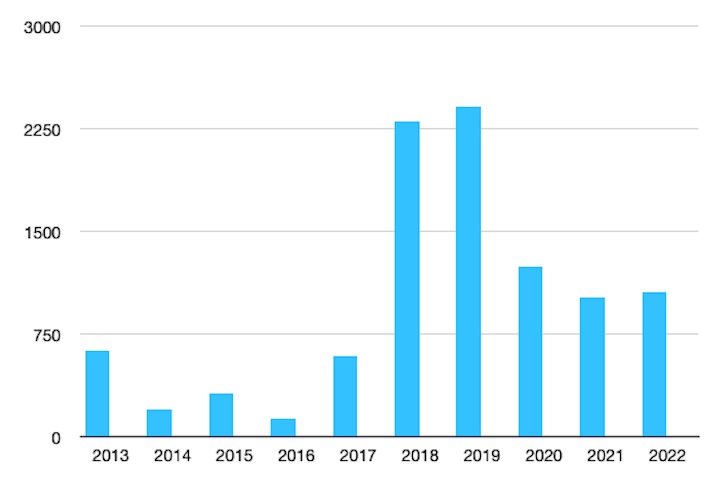

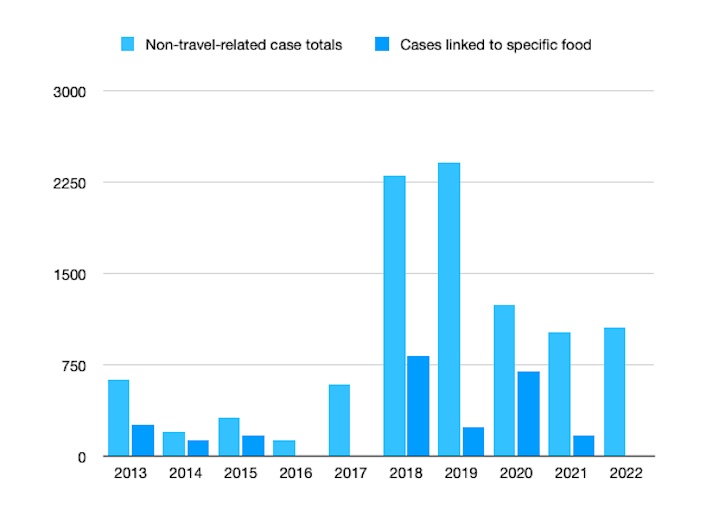

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) tracks the number of NTR Cyclospora cases reported each season, which runs from May to September, and publishes monthly updates. Here’s what those annual totals look like over the last 10 years:

Source: Food Poisoning Bulletin with data from the CDC.

Humans are the only known reservoirs for Cyclospora. So when people develop cyclosporiasis, it means they have consumed food or water contaminated with human feces containing the parasite.

Symptoms of this infection, which include explosive and watery diarrhea, abdominal cramps, bloating, nausea, loss of appetite, weight loss, and fatigue usually appear within 1 to 14 days of exposure. Without antibiotics, they can last for months.

Human Feces, Toilet Paper in the Fields

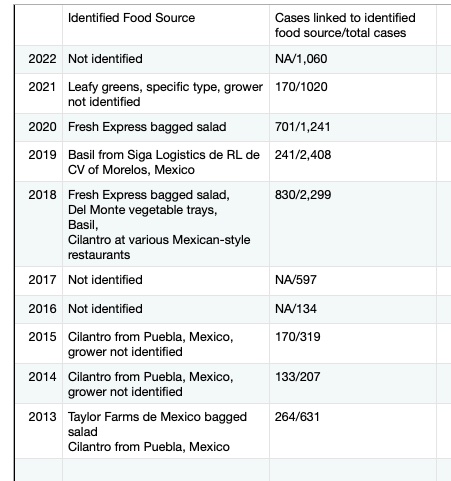

Many Americans first learned about Cyclsopora in 2013 when two large outbreaks sickened hundreds of Americans. One was linked to a salad mix produced by Taylor Farms de Mexico and sold at Red Lobster and Olive Garden restaurants. The ingredients for the salad mix were grown in Puebla, Mexico, the same region where fresh cilantro, the source of the other outbreak, was grown by a company unnamed by health officials. Together, these two outbreaks accounted for about half of the 631 cases reported that year.

In 2014 and 2015, a significant number of the total NTR Cyclospora cases were also linked to cilantro from Puebla, Mexico. The repeated outbreaks prompted officials from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Mexican regulatory agencies to visit and inspect the farms where the implicated produce was grown.

The conditions they found there prompted the FDA to issue an import alert on July 28, 2015. This action bans almost all cilantro grown in Puebla from entering the U.S. between April 1 and August 31 annually. (In 2022, two companies have met the stringent requirement to be exempted from the ban.)

According to the alert, inspectors observed “human feces and toilet paper found in growing fields and around facilities; inadequately maintained and supplied toilet and hand washing facilities (no soap, no toilet paper, no running water, no paper towels) or a complete lack of toilet and hand washing facilities; food-contact surfaces (such as plastic crates used to transport cilantro or tables where cilantro was cut and bundled) visibly dirty and not washed; and water used for purposes such as washing cilantro vulnerable to contamination from sewage/septic systems. In addition, at one such firm, water in a holding tank used to provide water to employees to wash their hands at the bathrooms was found to be positive for [Cyclospora].”

In 2016, the first year a full season of the import alert was in effect, Cyclospora cases in the U.S. plummeted to 134, a number on par with the annual average of 150 cases reported prior to 2013. The FDA did not identify a source of the illnesses but attributed the overall decline in cases to its efforts citing the import alert, increased testing, industry outreach, and prevention strategies with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

But in 2017, cases shot right back up again.

Neither the CDC nor the FDA offered an explanation for the increase in case numbers or what food source was associated with the 597 NTR Cyclospora infections reported between May and October of 2017. And that was the last year, the seasonal total would include fewer than 1,00 cases.

The Call is Coming from Inside the House

In 2018, 2,299 NTR Cyclospora cases were reported between May and August. About a third of them, 761, were attributed to two large outbreaks. One was linked to Fresh Express bagged salad sold at McDonald’s, the other was linked to Del Monte vegetable trays sold at Kwik Trip stores.

Smaller clusters of illnesses were linked to herbs. Two states, that the CDC did not identify, reported eight-person clusters linked to basil. And 53 illnesses were linked to cilantro served at various Mexican-style restaurants that were not named by health officials. When the CDC published its final report on the outbreaks in October 2018, the FDA was still in the process of conducting traceback investigations. No follow-ups were posted.

Until these outbreaks, the FDA had been working under the assumption that NTR Cyclospora infections were only associated with imported produce, according to Samir Assar, Ph. D, Director of the Division of Produce Safety (DPS), at the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN). “When we found the parasite in domestically grown produce, we recognized that we needed more tools and expertise,” he said in published remarks last year. Part of that approach included the formation of a Cyclospora task force in 2019.

Testing 1, 2, 3

In addition to the two large outbreaks in 2018, another factor that played a role in the 285 percent increase in NTR Cyclospora cases from 2017 was an increase in diagnostic testing, according to the CDC report from that year.

While health officials were ramping up diagnostic testing on patients, the FDA had a testing breakthrough on product samples. Using a new testing method, the FDA found Cyclospora in salad mix that had been sold at McDonald’s restaurants. This was the first time in almost two decades that the agency was able to confirm the presence of Cyclospora in food. A method successfully used in the late 1990s and early 2000s was no longer available after necessary supplies and equipment stopped being manufactured, Research Microbiologist Helen Murphy explained in the 2018 announcement.

“This new method not only provided us a way to detect Cyclospora once again, but advanced the technology beyond the testing we used in previous years to provide better analytical tools with greater sensitivity to detect Cyclospora on fresh produce. This helped us connect the dots and supported CDC’s epidemiological findings about the likely source of illness. The laboratory results were consistent with the other available evidence, giving us a much stronger case for taking regulatory actions, if needed,” said Alexandre da Silva, Ph.D, Senior Biomedical Research Service Research Microbiologist and Lead Parasitologist at CFSAN’s Office of Applied Research and Safety Assessment said in the same announcement.

With increased clinical testing and a validated method for detecting Cyclospora in food samples, one might expect to see an upward trend in cases linked to outbreaks. But one other thing that first happened in 2018, and has continued each year since, was the CDC’s inclusion in its annual Cyclospora reports of language like “many cases of cyclosporiasis cannot be directly linked to an outbreak, in part because of the lack of validated laboratory “fingerprinting” methods needed to link cases of Cyclospora infection. ”

Health officials use whole genome sequencing tests to identify the genetic “fingerprint” of particular bacterial strains. This allows them to link cases to one another and to a food source. But the type of test used for bacteria such as E. coli and Salmonella can’t be used on Cyclospora, primarily because of its size. The Cyclospora genome is ten times larger than a bacterial genome and it’s rare to obtain that much DNA from patient stool specimens or product samples.

Other challenges to genomic research of Cyclospora have to do with its unique properties and what scientists describe as the parasite’s elusive nature. Cyclospora only replicates while it’s inside a human host and is then shed sporadically in small amounts in the host’s stool. This makes it challenging to get enough organisms to study because, unlike bacteria, Cyclospora can’t be grown in lab settings.

Despite these challenges, the FDA and CDC have been working together to develop genotyping methods that will genetically link cases of illness to one another and to product or environmental samples, according to the FDA’s Cyclospora Prevention, Response and Research Action Plan current as of July 25, 2022. “This methodology is the only one available for genetic typing characterization of [Cyclospora]. These genotyping tools will be available for the first time to assist with outbreak investigations in 2022,” the document states.

But all of these testing breakthroughs haven’t resulted in high numbers of solved outbreaks.

Source: Food Poisoning Bulletin from state and federal sources.

2019 and Beyond

In 2019, the CDC reported the highest-ever number of NTR Cyclospora cases in one season. Between May and August, 2,408 Americans were diagnosed with cyclosporiasis. In its final report on the season that year, the CDC again stated that the increase was due, in part, to more diagnostic testing.

It also added that “many cases of cyclosporiasis could not be directly linked to an outbreak, in part because of the lack of validated molecular typing tools for [Cyclospora], the parasite that causes cyclosporiasis.”

In 2019, only 10 percent of illnesses reported were associated with a specific food source, the 241 cases linked to basil imported from Mexico by Siga Logistics of Morelos. Nothing about food produced domestically was reported. One of the monthly updates that year said multiple clusters associated with different restaurants were investigated, but those names were not released.

What was the source of the other 2,200 illnesses that year?

In 2020, the total number of NTR Cyclospora cases dropped to 1,241. The CDC did not provide an explanation for the dramatic decrease.

Fresh Express bagged salad was linked to another outbreak that year. The outbreak ended in late September after sickening 701 people in 14 states. A month later, the FDA sent the company a warning letter citing the company’s lack of preventive controls, grower/harvester verification activities, and delay in providing the agency with documents needed for a traceback investigation.

The 2020 Fresh Express Cyclospora outbreak accounted for about 56 percent of the 1,241 cases reported that year. It was the last time a specific food product was linked to a Cyclospora outbreak.

In 2021, 1,020 Cyclospora cases were reported. Leafy greens were cited as a source but the FDA could identify a specific type or grower. This year 1,060 cases were reported. No products were linked to any of these illnesses.

If you have been diagnosed with a Cyclospora infection from contaminated food, please contact our experienced attorneys for help with a possible lawsuit at 1-888-377-8900 or 612-338-0202.