The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed an interactive online program so consumers can track foodborne illness outbreaks over a 20 year period. The tool is called FoodNet Fast.

The database includes confirmed cases of infection reported to FoodNet, which is the CDC’s Foodborne Disease Active Surveillance Network. It includes outbreaks from 1996 through 2015. People can search by year, pathogen, age group, sex, and race.

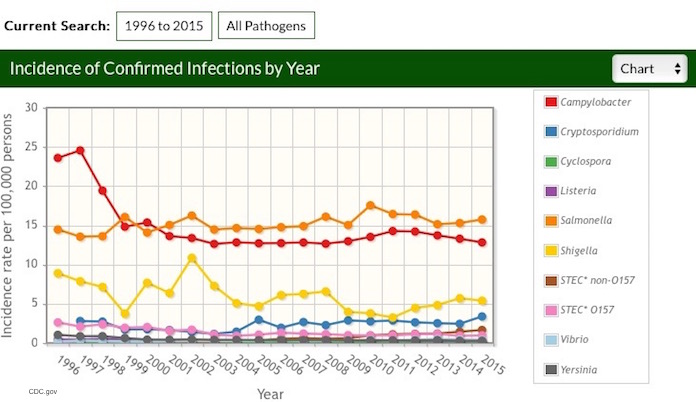

To develop the database, officials used surveillance from FoodNet in 10 sites for infections of nine pathogens that are commonly transmitted through food, and also for hemolytic uremic syndrome, a complication of E. coli infections that can cause kidney failure. The database also tracks how the rates of illness for Campylobacter, Cryptosporidium, Cyclospora, Listeria monocytogenes, E. coli, Shigella, Virbrio, and Yersenia have changed in the last 20 years.

CDC spokeswoman Brittany Behm said in a statement, “the tool also provides information on seasonality, hospitalizations, deaths, ethnicity, international travel-associated cases and outbreak-associated cases. Users can see species or serotype information when viewing a single pathogen. An FAQ provides guidance on using the data and limitations to keep in mind.”

The database was created to help consumers, and also so that public health workers, consumer advocacy groups, the medical community, and the food industry could learn about outbreaks. Searches can be customized by pathogen, year, age group, sex, or race.

At this time, FoodNet Fast only includes information on confirmed cases. That means that the bacterium in question was isolated from a patient’s specimen. Information on probable cases will be included in the future. That includes cases with positive lab results without culture confirmation.

FoodNet Fast does not identify all cases of illness and does not give a complete picture of all of the foodborne illness cases and outbreaks in the United States. Many people who get sick with food poisoning do not seek medical care, and some may not be tested for a specific pathogen. The only way that outbreaks can be identified and traced is if people tell officials about their illnesses. In fact, only about 3.3% of all people sickened with Salmonella infections are identified, and about half of all people with E. coli infections are identified.