E. coli lawyer Fred Pritzker is representing people sickened in the deadly E. coli O157:H7 (STEC) HUS outbreak that is linked to romaine lettuce from the Yuma, Arizona growing region. We asked him about the outbreak. “With almost 200 people sickened across the country, this is the largest E. coli outbreak of 2018,” says attorney Pritzker.

Eighty-nine people sickened in the outbreak have been hospitalized.

“The CDC is reporting 26 cases of hemolytic uremic syndrome, referred to as HUS, associated with this outbreak. HUS damages the kidneys and often causes renal failure,” says Pritzker. “The pain and suffering associated with these cases is off the charts.”

Five people have died, and Pritzker says these families should contact an E. coli lawyer about a wrongful death lawsuit. The deaths occurred in California (1), Arkansas (1), Minnesota (2), and New York (1).

This severe and deadly Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) outbreak is the largest of its kind in the United States in more than ten years. And the FDA and CDC have not been able to identify growers, processors, packers, or distributors, or grocers or restaurants who sold it to consumers, despite a lengthy investigation.

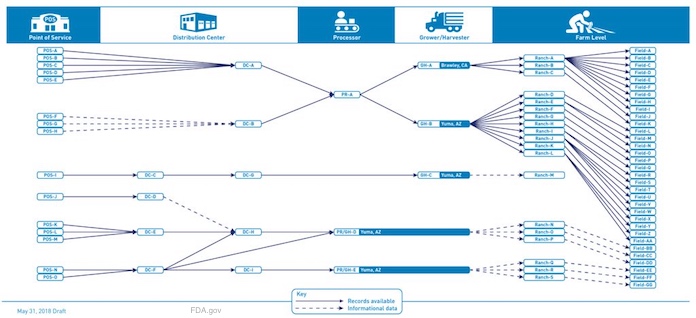

There are at least 33 farms that grow the lettuce in the Yuma, Arizona region, three harvesters, three processors, five distribution centers, and 16 points of sale on that chart. One lot at a production center can contain romaine lettuce from many different farm fields. Just a few contaminated heads of lettuce can contaminate an entire production lot. One facility, Harrison Farms, was identified as the source of whole-head romaine that sickened inmates at a correctional center in Alaska. But no other facilities have been identified. And no grocery stores or restaurants have been named by the government.

We asked Fred why government officials have not been able to solve this outbreak. He said, “Lettuce is a perishable product. Romaine lettuce may have a 21-day shelf life, but once it is served in a restaurant, it’s quickly discarded. By the time people get sick, go to their doctors, are tested for an E. coli infection, and that infection is diagnosed and reported to public health officials, weeks have usually passed. The evidence has disappeared.”

E. coli lawyer Fred Pritzker, who has successfully represented many clients sickened with E. coli O157:H7 infections and HUS, said, “Even when you recover from this infection, there is still a risk you will develop a serious complication in the future.” To contact Fred Pritzker, call 1-888-377-8900 or 612-338-0202.

“Second, the chain from farm to fork is very complicated, especially in the produce sector. Traceback is convoluted. Just one broken link in the chain can thwart entire traceback efforts.”

“Just think about it,” Fred continued. “Farmers grow and harvest the lettuce. The romaine lettuce in this outbreak may have been contaminated at the very beginning in the field from animals defecating, from contaminated irrigation water, or from runoff from factory farms. That means the lettuce could have contaminated processing and harvesting equipment and shipping containers. Then it’s easy for the bacteria to spread throughout the processing and distribution system and contaminate many bags of the final product.”

“Or the lettuce could have been contaminated in the packing containers, or in the large facilities that clean, chop, and bag the product for restaurants and grocery stores to buy and sell. The redacted distribution chain that the FDA released last week illustrates just how complicated this matter is.”

We asked Fred how consumers can protect themselves. He said, “Pay attention to recall notices, and to any outbreak notices. Every piece of food sold in this country can potentially be contaminated. But keeping up to date on current concerns and outbreaks can help keep your family safer. Many people still don’t know about this outbreak, after weeks of publicity. And follow safe food handling instructions provided by experts. And if you do get sick, see your doctor.”