The E. coli O157:H7 HUS outbreak that is linked to romaine lettuce from Yuma, Arizona has baffled investigators. One farm, Harrison Farms in Yuma, has been named as the source of lettuce that sickened eight people in Alaska. But other than issuing a blanket warning about romaine harvested in the Yuma region, no distributors, farms, processors, or stores have been named.

As of May 2, 2018, there are 121 people sick in this outbreak. Fifty-two people have been hospitalized. Fourteen have developed hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), a type of kidney failure. And one person, who lived in California, died.

Briefly, the New Jersey Department of Health named a restaurant that may have served some of the romaine lettuce that made people sick. But the CDC and FDA have not named that facility. No recalls have been issued.

So what’s going on? Why has this outbreak been so difficult to trace? Restaurants, processors, distributors, harvesters, and farmers are all supposed to keep detailed records of the products they produce, ship, and sell to the public. Why has traceback been so elusive in this outbreak?

Food Poisoning Bulletin asked Fred Pritzker why this outbreak has been so difficult to crack.

If you or a loved one has been diagnosed with an E. coli infection, you can contact attorney Fred Pritzker for help by calling 1-888-377-8900 or 612-338-0202.

He said, “The transitory nature of a product like this is one reason. And the contamination could have occurred anywhere along the food chain. Finally, equipment used to harvest and process the lettuce was cleaned after the romaine harvest ended, washing away any contamination.

And here are multiple distribution channels for this type of product. In the distribution system in the U.S., lettuce from farms all over the country are shipped to a few distribution centers, where they undergo processing. If a couple of heads of romaine are contaminated, when they are washed, chopped, and mixed, the contamination can spread. And the more the lettuce is processed, the more complicated the trail.

The regulations rolled out with the Food Safety Modernization Act of 2011 have not been fully implemented. Those regulations aren’t enforced with inspections yet. Farmers are still being trained in produce safety. And the first inspections of the biggest farms in this country will not begin until 2019.

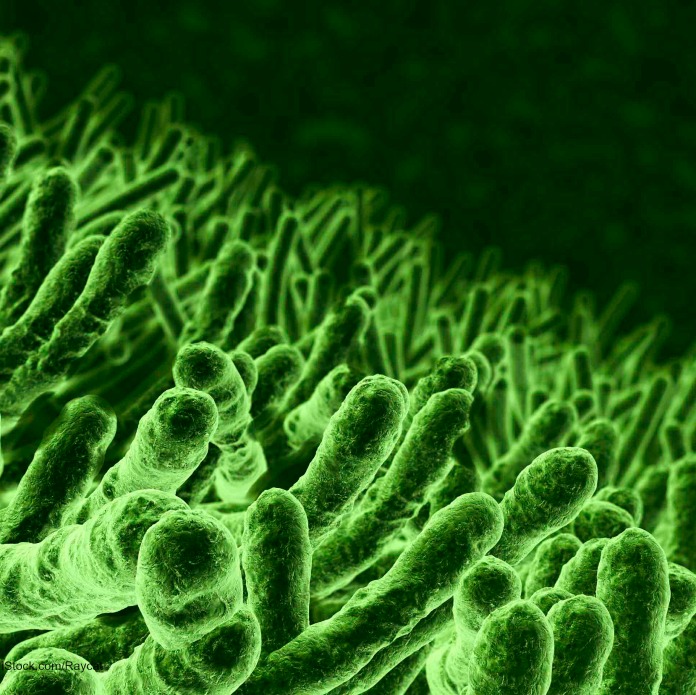

The lettuce was probably contaminated by fecal material that came from a ruminant animal. But was that bacteria in irrigation water? Was runoff from a nearby factory farm the factor? Did the bacteria come from wild animals in the field? Was a shipping container contaminated, or a harvesting machine? We may never know.

It’s still a good idea to avoid romaine lettuce for the time being. The growing season in Yuma ended in March. As time goes by, not only will the trail grow cold, but it will become safer to eat romaine lettuce again.

The noted law firm Pritzker Hageman helps people who have been sickened by contaminated food protect their legal rights and get answers and compensation. Our lawyers help patients and families of children in personal injury and wrongful death lawsuits against schools, retailers, grocery stores, food processors, restaurants, and others. Attorney Fred Pritzker recently won $7.5 million for a young client whose kidneys failed because he developed hemolytic uremic syndrome after an E. coli infection. You should know that class action lawsuits may not be appropriate for outbreak victims because each individual case is different.